How can we travel without contributing to global warming?

I’ve been considering this problem for a while at the institutional and macro levels, as I researched climate change and higher education’s future. I’ve also mulled it for myself, thinking of how to decarbonize my professional travel, mostly recently in 2022. Since then I’ve made some changes and also hit some obstacles, and want to share where things have ended up today.

Two quick introductory notes: first, for context, I live in Manassas, Virginia, right near Washington, DC. I have traveled extensively for professional reasons, heading to locations to give presentations, lead workshops, facilitate or be in meetings, work conferences, conduct research, and so on. This has led me throughout the United States and to every continent except Antarctica. I am also a very busy person who does a lot of work online, which means I need to travel quickly and/or with opportunities to work.

Second, some people have told me not to bother analyzing and redesigning my travel, the main argument being I’m just one person with a statistically infinitesimal impact on the globe. This is true on the face of it, but I’m otherwise unconvinced. The obvious counterargument is that the climate crisis is a civilization-wide thing, an all of the above, all hands on deck kind of event. Everyone gets to participate and should. Moreover, and perhaps vainly, I hope I can stir some discussion with this work, and perhaps even convince others to decarbonize.

The problem is complicated, so I’ve broken it down into three levels of increasing difficulty.

DALL-E imagines decarbonized travel.

1 The local situation is quite doable

Walking doesn’t get me to most places, as we live in a residential district. There is a shopping cluster about one mile away, complete with basic grocery store, drugstore, urgent care, and public library branch, so that’s doable on foot, depending on weather. The town of Manassas proper is about an hour’s walk each way.

So I bike, and that’s fine. My current range is about 5-6 miles out since I restarted biking a couple of years ago. I can carry some stuff in panniers and a backpack, which lets me do a good number of errands involving moving objects to and fro: groceries, our gym, library book club, medications, a bookstore, some clothes shops, medical clinics, two post offices, the DMV, even the nearest hospital. I wear bone conducting headphones so I can listen to podcasts and ebooks while hearing the immediate environment – i.e., listening for cars.

Yet none of this is professional travel. Ranging further afield for that purpose requires a mix of bike, trains, and some cars. Virginia’s commuter rail line actually ends 3 miles from our house, and there’s another station in town just 2.5 miles away, so I can easily bike to that and ride into Washington, DC. The only problem is that the VRE has extremely limited hours, basically brief early morning and later afternoon slots, and those only on Monday-Friday. This is an issue when my schedule doesn’t fit; for example, many of my Georgetown classes are evening ones.

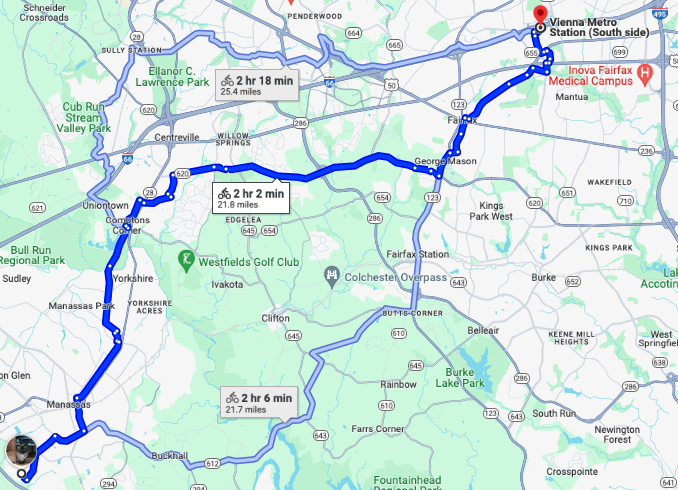

Washington’s famous Metro is another option, and works brilliantly except for one problem. In my experience it’s pretty reliable and low cost. Best of all, I can do work while I’m riding. The problem is that the nearest station is about 22 miles away. It’s a two hour+ bike ride through some difficult roads.

That’s beyond my biking abilities so far, but I’m working on it, pushing myself to extend my range. If I can make it work, it might yield a new problem in terms of spending 4-5 hours on the road for each Metro trip, basically adding a commute to a commute. I can get a little work done on the bike, but only through listening to podcasts and audiobooks. In the meantime I have to drive or Uber to the Vienna station. From there it’s good.

How does this work professionally? For one, Washington is a magnet for meetings, due to its importance. Throughout the year I head into town to meet with clients, some of whom even have a DC office for this kind of thing. For another, I can reach other transportation mechanisms this way. Let me explain…

2 The medium-scale situation is challenging

In many ways trains are the among the least bad carbon generators in the transportation world. They don’t spew as much CO2 into the air as jets do. Per person they can have a smaller impact than cars.

Unfortunately, I live in the United States. The reason this is a problem is because our national passenger rail provider, Amtrak, is… not great. For reasons of time I’ll skip over how and why this came to pass, and instead sketch the present situation.

To start with, its coverage is quite limited for the sheer size of the United States. Consider this official map:

You quickly see big swathes unserved, including entire states. Some of the routes are strange, too. For example, to travel from New York City to Detroit requires a ride which skips right past the entire state of Michigan, heads west and north to Chicago, then switches back to reach Detroit from the other side. As a result we have to build in significant car travel to train rides, which returns us to the carbon problem.

Then there’s the ride quality issue. I don’t mean comfort. I do enjoy having electrical outlets and a far easier boarding process than airports provide. What is an issue is timing and reliability. Most of these trains are *slow*. They also often experience delays. I’ve had four-six hour trains delayed by 1, 2, 3+ hours.

Don’t take my word for it. Amtrak’s own data doesn’t look good:

When the very best train only scores 75% on time and a bunch are under 50%, this is an issue.

The reasons for this awful quality problem are well known. Freight trains often muscle passengers out of the way, hogging lines and slowing traffic. The train ecosystem is a complex one with many essential parts; America’s refusal to take infrastructure support seriously means that engines, cars, rails, and other parts fail more than they should. And climate change is now making things worse, as tracks can become too hot for smooth travel.

As a result, this is a major problem for business travel. I can’t just pop across several states for a meeting. Instead I have to allocate at least two full days for travel, there and back. Worse, riding trains isn’t a great working experience. Amtrak’s WiFi is laughable, so we can use hotspots (either phone or separate hardware), but cell phone coverage is patchy along train lines. My current practice is to have a stack of ebooks and pdfs on my laptop for reading when the internet just stops working. And to avoid video meetings and even phone calls.

Worse, there’s a range problem. Let me explain:

3 Long range travel is unsolved

In my work I travel across the United States, as said earlier. Surely I could take Amtrak across this broad nation, right?

Wrong. Let’s start with the problems mentioned before, of slow speeds, frequent delays, and an iffy working environment. These are multiplied once we look at traveling not hundreds but thousands of miles. To pick a very long trip, Amtrak posts a schedule for traveling from Washington to Los Angeles of 67-88 hours. DC to San Francisco? 77-78, involving three separate trains and two bus rides. That’s the posted timeline; the reality of delays means even longer rides still.

Worse, we hit the problem of missed connections. Air travelers are all too familiar with challenging layovers. Amtrak somehow manages to make this worse. If the first leg of a trip falls behind schedule, and we’ve seen that this is likely, then it’s easy to miss the second. Unlike air travel, American passenger trains have very few runs, meaning a broken connection can add another day to your trip.

I’ve experienced this myself too many times. One DC-to-Ohio trip routed through New York City and had a two hour layover. My first train started off late, then hit another delay, and then another. Conductors assured me I’d be fine, but when I leaped out of the door at Penn Station the second train had already departed. Amtrak staff baldly told me I blew it and had to wait 24 hours for another chance. (I ended up having to take a plane, since my client needed me there the next morning.) For another example, I nearly booked a DC-to-Maine train, only to find a 16 minute connection in Boston. Not only was that layover comically short and easily broken, but switching between trains involved a more than 1 mile run between two different stations. For business travel, I think the only way to handle this realistically is to add in an extra day of travel each way. Which is not good.

Worse, from a purely climate perspective, Amtrak outside of the eastern seaboard tends to run on diesel, rather than electrical power. So this decarbonizing effort ends up recarbonizing.

My conclusion now is to take trains as far as they practically go, which means a chunk of the United States’ eastern region. That means not taking trains for long distance.

How else can we travel long distance?

I’ve been starting to look into ships and haven’t had much luck so far. Crossing the Caribbean, the Atlantic, or even the Pacific isn’t easy. Passenger ships are slow, expensive, have uneven internet access. Cruise ships might be more comfortable but are CO2 nightmares. Freighters might be better on this score, but lose out on comfort and, again, connectivity.

Hybrid and electric vehicles would follow the classic American love of cars. The country is designed for that. I also have a personal reason to consider road trips, which I don’t feel ready to divulge at this moment. Yet the time is immense in driving across this huge country, and doing work while driving is basically a nonstarter.

Which brings us to air travel. This seems to be the only way I can reach destinations beyond the United States and eastern Canada. Yet it is a CO2-spewing machine. So what to do?

Carbon offsets have been one solution since the 1990s. They involve paying someone to promise to sequester CO2 in a safe location to balance out someone else’s emission of the same. It’s a tradeoff based in market logic, so very much a post-Cold War kind of plan. It has a lot of adherents, including a large number of non- and for-profits purporting to set aside that carbon. I’ve been to conferences where vendors have offered to purchase attendees’ measures of travel-generated CO2.

Offsets have not turned out well in practice. The market is not well regulated or even supervised, allowing for all kinds of mistakes and scams. Sequestered carbon is vulnerable to not being sequestered – i.e., someone can set aside a splendid forest, only for it to suffer a fire. CO2 storage may be located in marginalized communities. Then there’s the moral risk of people happily flying around the world, consciences assuaged by offsets, as the climate crisis worsens, when instead we should be reducing emissions at top speed.

At the very least we have the issue of trying to determine the best, or least problematic, offset. In a market lacking transparency, standards, and regulation, this is a significant lift.

Here’s one video diving into the problems:

Perhaps there’s an alternative to offsets. I could fly, then ask my hosts to donate money to good groups working on climate change. Doing so would also take some research. It might be tricky to convince clients to help fund certain groups, especially if they seem politically unpalatable. (Think about asking a state institution to support Greenpeace, or a private campus with significant oil industry investments to give to Scientist Rebellion.) Such donations leave the CO2 on the table – or, more precisely, lofted into the atmosphere.

Here’s my current set of options for travel beyond basic train range:

- Fly. Argue that the good work I do outweighs the carbon cost. I don’t know how to quantify the former sensibly.

- Fly. Spend a good amount of time researching offsets and pick the least bad one, such as Gold Standard. Build that cost into my fees.

- Fly. Select a good and effective climate action group, then build donations to it into my fees.

- Refuse to fly. Instead, do video, either synchronous or prerecorded, depending on time zones.

Honestly, #4 strikes me as the most ethical option at this moment. It takes the climate crisis the most seriously and I am seriously considering it. It’s an extreme position, and so entrails risk. It could burn bridges. It might also be a major blow to my work, as many paid engagements have required air travel. Virtual engagements have yet to make up the difference. But I can double down on them and perhaps, seen as an alternative to high carbon emissions, people will accept them. Who else is doing this? Is there a name for it?

“At this moment”: the situation is changing. These options might be temporary.

4 Looking ahead

There has been tremendous research and development in decarbonization. Solar power has become a world-winner, as Bill McKibben keeps reminding us. Hybrid and straight up electric vehicles have become consumer vehicles, although the US-China Cold War 2.0 seems to make that both easier and harder at the same time. Shouldn’t we expect more transportation progress?

Another DALL-E decarbonization vision.

Americans trains seem, alas, stuck. Improving and expanding Amtrak would be a massive, massive undertaking, requiring huge cash investments, obtaining permissions for thousands of miles of track, switching out trains, and more. Politically this has reliably proven a failure. President Biden, a long-time Amtrak rider, apparently tried to do something along these lines, but lost the chance in negotiations. Making Amtrak more viable sounds like at best a long term strategy.

There’s a lot of work going on to decarbonize air travel. People are working on alternative fuels, lighter batteries for electric planes, solar-power aircraft, and new fuselage designs including “shark skin.” These are all in the earliest stages for now, and we should expect years before they roll out.

As a Kim Stanley Robinson fan I love the idea of airships, if they can become consumer-accessible and also internet-equipped. This hasn’t transpired, sadly, and I’m not sure if the helium supply problem will block this.

For working while traveling, there are various reasons for poor connectivity to exist in the United States, starting with financial incentives and continuing with ISPs being fundamentally disinterested in expanding access. Perhaps trains will contract with Starlink to improve access coverage. Maybe cell phone network reach and speeds will incrementally improve enough to spill over onto railroad lines.

How might offsets get better? We could see parallels from other fields. A trusted, third-party source might appear which vets offset quality. International agreement could set up standards or even certification.

Back on the car front, I’m curious about when self-driving hybrids or EVs become available. Riding one of those vehicles from, say, Washington DC to South Dakota might be appealing. Being freed up from having to be at the wheel most or all of the time lets me get work done (I’ve found better cell phone coverage on roads than rails) and being hybrid/EV could reduce the CO2 footprint.

Looking ahead in other areas, will people in the academic space change their attitudes? For example, how willing will clients be to pay for offsets or climate action groups? Right now I can see the former being popular, but perhaps colleges, universities, governments, companies, nonprofits, etc. will turn against them unless quality improves. For the latter, will some groups become popular in the academic space? How many are prepared to do blended/hybrid meetings in a competent, or even excellent way?

For another example, will such entities become interested in chaining several events together in order to minimize travel? Already we have the precedent of professional associations co-locating events back to back when they have a common audience. Many people use conferences to stage meetings. Perhaps we can expand to have, say, a week of meetings.

Or will academics and the academically-adjacent become more accepting of virtual events? Perhaps I can lean into this, calling for, and helping establish a top level standard for synchronous video.

At a bigger, more civilizational level, will we become accustomed to lower levels of travel? Some visions of the Anthropocene see us as a more localized species, visiting neighbors but going farther afield less often. Perhaps in-person events will become more rare and thereby more special, reserved not for annual conferences or ordinary meetings but for the extraordinary gathering.

That’s where things stand for me. What do you think? How are you considering your own travel in light of climate change?

(many thanks to friends on Patreon, Facebook, and the Association of Professional Futurists for conversation on this topic)